The new praxis for the removal of architectural barriers

“The quality of urban life derives from the mix of the quality of the environment, architectural spaces, economic conditions, welfare and social cohesion. A city with a good quality of life is a city in which everyone is able to develop his/her own potentialities and to have a serene and satisfactory life. The quality of urban life also depends from the possibility for citizens to take advantage of resources and services, and granting them the relationships they consider fundamental for their social life. Then, accessibility must improve the comfort of urban areas, by removing all the obstacles which create discriminations, in order to favour equal opportunities”.

This is the starting point of the “Prassi di riferimento (Reference praxis) UNI/PdR 24:2016 – Removal of architectural barriers – Guidelines for redesigning the built environment according to universal design principles”.

The Universal Design concept is based on seven main principles:

- Equitable use

- Flexibility in use

- Simple and intuitive use

- Perceptible information

- Tolerance for error

- Low physical effort

- Size and space for approach and use

The “Praxis” was presented in a press conference on February 2nd this year. It was born thanks to the cooperation between FIABA Onlus, CNGeGL & UNI1. The paper was presented by Giuseppe Trieste, Piero Torretta and Maurizio Savoncelli, respecitvely president of FIABA, UNI and CNGeGL. Some high level public authorities also participated: Ilaria Borletti Buitoni (Vice Minister of Cultural Heritage, Culture and Tourism), Cosimo Ferri (Vice Minister of Justice), Riccardo Nencini (Vice Minister of Infrastructures and Transports), Paola Iandolo (representing the Ministry of Education and Research) and Alessandro Cattaneo (president of Fondazione Patrimonio Comune ANCI2).

THE REFERENCE PRAXIS

“Praxis UNI/PdR 24:2016” is a guideline and not a standard3. Its scope is to provide a number of technical guidelines for the re-design of the built environment, according to the “universal design” principles. The paper provides a methodologic approach, based on the “accessibility for all” concept:

context analysis (there included the use of the environment);

critical issues detection methods (there included the criteria to individuate architectural and sensorial barriers);

design approach analysis (definition of the budget for the removal of the architectural barriers).

The new “Praxis” describes some possible technical solutions to eliminate the most common critical issues when removing the architectural barriers, indicating the proper legal tools, the voluntary regulation standards and/or the good practices already adopted.

The guidelines are applicable to all contexts, such as urban spaces (pedestrian paths and areas, green areas, roads and streets, etc.), public and school buildings, leisure structures (sport, culture and theatres; hotels, temples, cultural heritage and museums; etc.).

The guidelines

The first guideline is “there are no groups of persons with characteristics to be categorised: there are only persons”, with their own qualities and peculiarities. Disability is not an issue for a minority of citizens, neither the only obstacle that a person might face during their life. Accessibility has many aspects and causes the raising of the quality of life for each individual, at any age, with a long term or temporary disability, visible or hidden, and to friends and families of disabled people.

The “Praxis” promotes the “total quality” concept, in order to reach a global and inclusive approach of accessibility and to the use of built environment. At this aim, the re-design of the built environment must start from the functional and anthropological analysis of how such space is lived and perceived. Then, a deeper analysis has to be carried out for the removal of architectural, physical and psychological barriers.

To use single standard is not sufficient anymore. The environment must be analysed with a global approach, with a holistic approach. The time of separated compartments, cost multiplication and missed targets is over. Such an approach is applicable to all contexts and is based on the removal of architectural barriers:

- in areas of cultural interest;

- parks and green areas;

- school buildings;

- urban paths.

At this aim, the “Praxis” identifies four specific phases:

- preliminary analysis (to check the need to remove architectural barriers);

- critical situation identification methodology (inspection, photographic survey, planimetry and altimetry survey, identification of possible solutions);

- design choices analysis;

- technical solutions identification, applicable to the most frequent cases (i.e. toilets, difference in height, multi-sensorial design, etc.).

Finally, from the standard view point, the “Praxis” refers to some Italian regulations4, to the European Concept for Accessibility (Technical Assistance Manual, EuCAN, 2003) and to some very well- known standards in our sector: EN 81-40 (Stairlifts and inclined lifting platforms), EN 81-41 (Vertical lifting platforms) and EN 81-70 (Accessibility to lifts).

Persons with impaired mobility

The “persons with reduced mobility” include the following categories:

- a) wheelchair users (persons who due to infirmity or disability use a wheelchair for mobility);

- b) people with limb impairment;

- c) people with ambulant difficulties;

- d) people with children;

- e) people with heavy or bulky luggage;

- f) elderly people;

- g) pregnant women;

- h) visually impaired;

- i) blind people;

- j) hearing impaired;

- k) deaf people;

- l) communication impaired (meaning persons who have difficulty in communicating or understanding the written or spoken language, and including foreign people with lack of knowledge of the local language, people with communication difficulties, people with sensory, psychological and intellectual impairments);

- m) people of small stature (including children);

- n) people of tall stature;

- o) obese people.

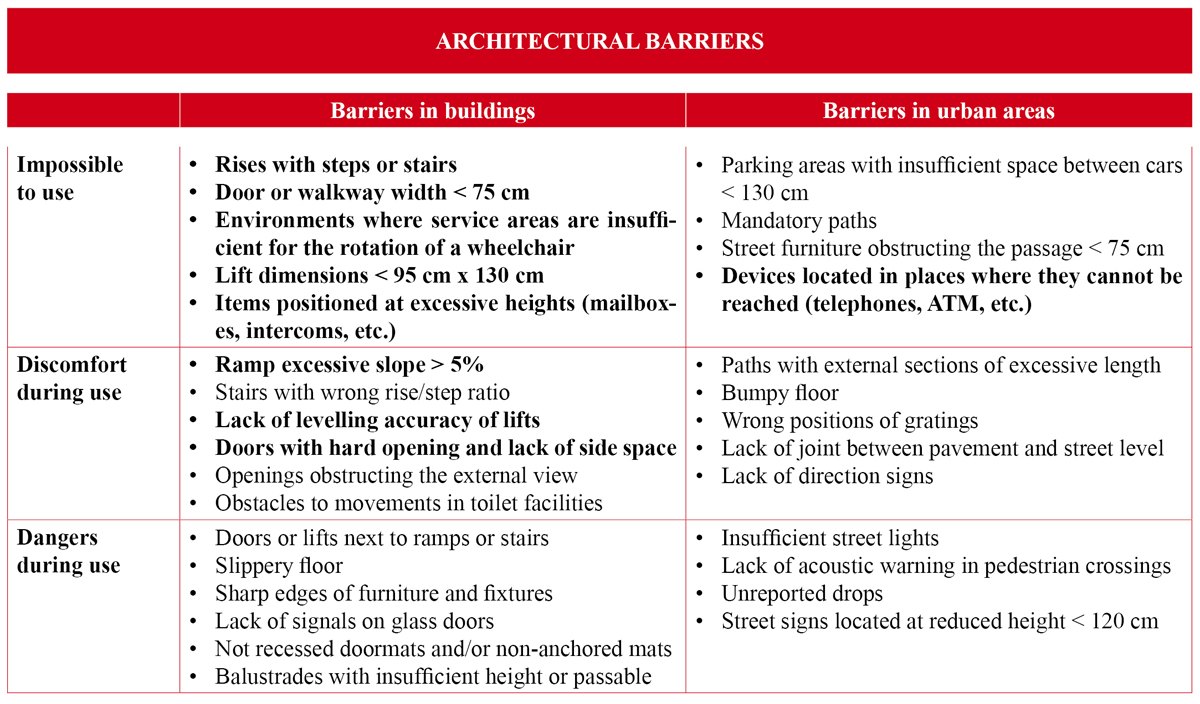

Architectural barriers

The “architectural barriers” are:

- a) physical obstacles that are a source of discomfort for the mobility of everyone, especially of those who, for whatever reason, have a reduced or impaired mobility, permanently or temporarily;

- b) the obstacles which limit or prevent anyone from comfortable and safe utilization of parts, components or equipment;

- c) the lack of measures and indicators that allow the orientation and recognition of places and sources of danger to anyone and in particular for the blind, for the visually impaired and the deaf.

Examples of architectural barriers in buildings

DIFFERENCE IN HEIGHT

In the chapter devoted to the technical solutions, the “Praxis” identifies the difference in height as the main problem, when redesigning environments to make them accessible to persons with reduced mobility.“The existing standard allows the possibility to realize differences in height, included between 2.00 cm and 2.50 cm. Nevertheless, in some cases, such difference is not practicable, then it might be better to provide completely flat paths. At the aim to resolve such critical aspects, the binding legislation provides designers with four possible solutions: ramps, lifts, lifting platforms and stairlifts”.The “Praxis” emphasizes the fact that, regarding lifts, lifting platforms and stairlifts, there are some Italian standards imposing compulsory maintenance (DPR 162/1999, etc.). Apart from the above- mentioned standards (UNI EN 81-40, UNI EN 81-41 and UNI EN 81-70), the document also explicitly refers to other standards: Lifts Directive (2014/33/EU), Machinery Directive (2006/42/EC) and the Italian Decree 236/89 for the removal of architectural barriers.The “Praxis” also suggests that “in addition, to the laws, it might be useful to accept tips deriving from the users’ experience (…) to provide guidance and suggestions useful to redesign height differences and ramps, in accordance with the universal design approach, highlighting the most common mistakes”.

Lifts

Par excellence, lift is the solution for all users.Lifts are useful for anybody and they might be used by anyone wishing to.Some problems might derive from space issues, limiting their diffusion, mostly in areas with reduced available spaces.It is appropriate to refer to EN 81-70 – if applicable – to fulfil technical and dimensional requirements.

Lifting platforms

Lifting platforms are a good solution in case of the need to upgrade existing structures, in presence of limited spaces or due to aesthetic/architectural constraints. In this case, the reference standard is UNI EN 81-41 to fulfil technical and dimensional requirements.Lifting platforms are slow, so they are less effective in case of longer travels.Their adoption might be very effective in the case of old and historical buildings.

Stairlifts

Stairlifts are a solution for single users. They need accurate maintenance due to their peculiar features. EN81-40 provides the technical and dimensional requirements.If it is not possible to adopt alternative solutions, the installation of starlifts is useful only for a limited category of persons with reduced mobility, excluding subjects with different impaired movements, such as families with baby strollers or people with luggage.

In terms of universal design, the installation of a stairlift to overcome a barrier is not an optimal solution, due to the law restrictions for the autonomous use.Nevertheless, in some cases, this might be the only possible solution.

Multisensorial design

“Adapting the built environment to the needs of all possible users means considering the people with reduced mobility but also people with impaired sensorial capabilities”. Some sensorial disabilities (blindness, visual impairment, deafness) are definitely an important issue even in the case of the use of vertical transportation means. Just think of the lift car and floor push buttons. In general and in the specific, the “Praxis” emphasises that “the multisensorial design constantly feeds on new information technologies and materials to implement its effectiveness”.

CONCLUSIONS

The conclusions are all in Giuseppe Trieste’s words: “The UNI Praxis has the great advantage to consider accessibility in function of human diversities. Each single human being, child, adult or elderly person has the same need to take advantage of the same possibilities. The Praxis – he said – will make the designers think of accessibility as a right, whenever they are making a new structure or refurbishing an existing one. Main entrance is a right for all!”.

Fabio Liberali